The Psychological Toll of Constant Demographic Change

"Resistance to any large change is not just natural, but driven by material biological factors, and powerful"

The concept of a New Year’s resolution has always fascinated me, because who these people that only ever think about radically changing their lives once a year? Personally, I exist in a state of eternal resolution, getting out of bed daily thinking - ok - time to get serious - no more wasting time - today’s the day I finally become who I was supposed to be. I expect to be doing this until my last day.

This is the comical and pathetic (in every sense) state most people exist in most of the time - perpetually desiring personal change, yet also perpetually remaining unchanged.

There is a reason you can’t stop eating late at night, or getting into arguments with your mother, or saying yes to commitments you can’t fulfill so on and so on, which is that inner barriers (habits, neuroses, neural pathways, hormones) are as concrete as outer ones. Because we can’t see the limitations we tend to convince ourselves they’re not there.

No person who is 5’9’’ would demand of themselves that they wake up tomorrow and simply start being 6’3’’, yet the weak are constantly demanding that they be strong, the cowardly that they be brave, introverted that they be extroverted and so on. And that’s only for the changes we want to make - it doesn’t even cover the difficulty of meeting changes enforced on us from outside.

One of the best examples of the reality of inner barriers is the new generation of weight loss drugs. Arguments about weight loss have generally revolved around willpower and still do but these drugs often change people’s perspective on this front. This is summarised by the following well-known quote from Oprah Winfrey on her personal experience:

One of the things that I realized the very first time I took a GLP-1 was that all these years I thought that thin people just had more willpower, they ate better foods, they were able to stick to it longer, they never had a potato chip, and then I realized the very first time I took the GLP-1 that, 'Oh, they're not even thinking about it. They're only eating when they're hungry, and they're stopping when they're full.’

By giving yourself a pinhead-sized dose of a fake gut hormone your whole inner world and capacity for change, changes. In addition to weight loss we know that the drugs appear to impact a variety of habits related to impulse control. In a post-GLP-1 world I don’t think we can simply point to people being too lazy to dial up their self-control as the main driver of obesity.

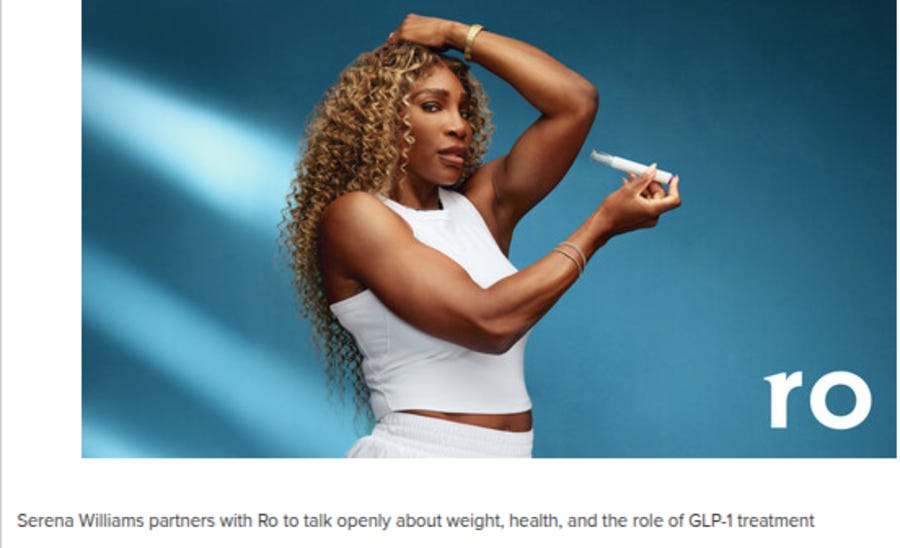

Being a storied athletic champion, Serena Williams must logically have more willpower in her little finger than you do in your entire body but she needed a GLP-1 to lose weight, or at least she felt that the effort was sufficient that that was a worthwhile way of doing it. (She is paid to promote them but also seems to have used them in her personal life.)

We had considered these problems to be psychological or spiritual in nature, and to be matters of personal responsibility, and of course they are. But what’s now impossible to deny is that our ability to manage these issues is subject to inner restrictions as real as a brick wall or the iron bars on a prison window - they just happen to be hidden. If we don’t talk about those constraints we’re not discussing the issue seriously. Resistance to change is not just natural, but driven by material biological factors, and powerful.

Let us consider the political implications of what I’ve written above.

In January Ursula von der Leyen proudly announced the conclusion of an economic deal between the EU and India, what she described as the “mother of all deals”. One aspect of the deal was that it will facilitate the movement of labour from India to the EU, thereby promising the prospect of a new wave of immigration westwards. In other words the pictures that issued from this meeting are of Ursula gleefully announcing more of the kind of policy that voters across Europe like the least, feel least capable of dealing with, and which is causing basic societal consensus to dissolve like a sandcastle under a frothy tide.

The normal explanation for why western leaders remain committed to the expansive immigration policies that their voters can’t stand is twofold - one that they are locked in to sustaining state structures that demand an ever increasing population of tax-cattle, the other is fanaticism about the idea of a borderless world. I don’t believe either of these are sufficient in and of themselves to explain the lack of self-awareness here. I don’t think the people who run these institutions are that philosophical, and I also think an instinct for electoral and systemic self-preservation should kick in at some point regardless of institutional commitments.

There is some kind of mind-blindness at play that is stopping powerful people from acknowledging that there are limits to how much change you can demand of people, and that there are psychological costs to changing the demographics of a society. I think it is that human tendency to deny that issues whose roots are worth taking seriously, or exist at all.

The blindspot that managerial liberalism has for psychological issues, or issues that are not purely material, is partial. Ritualistic acknowledgements of colonial guilt or white supremacy are not uncommon in European politics and speak to a philosophical hinterland. So we know they can do the touchy-feely stuff sometimes.

I think these ideas can be reconciled. From a governmental point of view, Immigration is necessary to make the GDP line on charts go up, and therefore so is the cultural and demographic change. The non-material implications become another slice on the pie chart to be accounted for, and you can outsource that management to specialist groups who will instruct you how to act. The system struggles to understand issues that can’t be reduced to a line on a spreadsheet, but it does understand stakeholder management.

Other than that, we’re governed by a heavily technocratic and managerial style of politics, which has the same flaws there that it does in a large organisation. The managers begin to confuse the things that can be measured with things that should be measured; and they stop believing in the existence or importance of things that can’t easily be quantified even when their personal human experience of them is staring them in the face.

The tendency to overvalue that which can be directly measured, and undervalue that which can’t, is a human problem that doesn’t just impact government bureaucrats. Even people who argue against mass immigration will constantly retreat to the safe territory of resource management, because we have the language to express dissatisfaction on those subjects. But the real trigger for dissatisfaction is often the upheaval and psychological disruption caused by the fact of these changes, and the scale of them, and not how the changes are being managed.

From a political point of view, the inner difficulties triggered demographic change have been explored by a couple of people. Robert Putnam’s “Bowling Alone” studies were considered revolutionary and are often cited but only because they provided an academic cover, in an American context, to admit something all normal humans already know. In a european context Putnam’s work only provides further illustration of points made by Emile Durkheim in the 1900s on the overlap between suicide and protestantism.

Durkheim used the term Anomie to describe the psychological tension that arises from a lack of agreed social and ethical standards. Cutting people loose from the seemingly irrelevant and burdensome demands of a settled culture isn’t always a nice thing to do and can have impacts on individuals up to and including feeling that you have no place in that society and that life isn’t worth living. Durkheim’s findings were part of a web of similar ones from the post Industrial Revolution era that have dripped into our discourse ever since, from Marx on alienation, and from writers like Ferdianand Tönnies and Georg Simmel on atomisation.

The point here is that, even if you didn’t know from just being alive and conscious, we have known this since at least the turn of the 19th/ 20th century that moving stable terrain of a society under the feet of the people while they’re standing on it has concrete and terrible consequences. That’s true even if you manage the purely practical impacts of that change, and even if we accept those changes (or the intentions behind them) are overall to the good. You can’t just move familiar things that give people’s lives context and meaning around and expect them to remain the same or remain happy, productive, calm.

What is the impact of demanding psychological change from people who are not inclined or equipped to give it? There is a difference between change we try to impose on ourselves and change that is imposed on us from outside. It helps to try and understand the demands of demographic change in the context of how we experience change in our personal lives. The difference is that in personal terms that change can be enforced on you at a personal level by a spouse or a parent or a boss but it’s rarely a person you voted for or against, or a person paid to represent you - which changes the dynamic somewhat.

If you insist on going ahead with a change you can’t manage then the output would be as follows. I asked AI to briefly summarise the literature on what happens “when demands for change exceed a person’s current capacity”:

… it typically triggers psychological reactance and profound shame, leading to defensive withdrawal or “shutting down” rather than genuine growth. This mismatch often results in a rupture of trust, as the individual feels fundamentally misunderstood and inadequate, which frequently reinforces the very behaviors the demander was trying to change.

Regression: The stress of impossible expectations can cause a person to revert to more primitive, less functional coping mechanisms.

Learned Helplessness: If they try and fail to meet the demand repeatedly, they may eventually stop trying to change altogether.

Relationship Erosion: The person being pressured begins to view the other party as a source of threat or judgment rather than a source of support.

I think this is accurate, and it explains a lot of the pathological aspects of our society and culture. “More primitive, less functional coping nechanisms” include riots, chants of “get them out”, confronting unwanted attention with machetes. “Learned Helplessness” certainly accounts for the withdrawal from society we see from young men in particular. “Relationship Erosion” is the one a professional politician, activist or journalist should fear the most, and that fear is justified - it seems obviously true that constant insistence on the public having no alternative but to be ok with intense demographic change is part of what has destroyed the relationship between the public and those institutions.

Everything about our personal experience affirms that change is both the most essential thing that a human must do, but also the hardest. The role of personal responsibility in relation to how we manage change, and how we react to it, is tricky. The lesson of weight loss drugs suggests that in many spheres it may not even be a factor, yet I would say it’s essential to continue believing in its primacy, especially for men. In any case we tend at both a personal and political level to gloss over the difficulty that demands for change cause in our lives, despite the evidence being everywhere. This natural tendency is accentuated by a managerial and technocratic (and quietly shallow) culture that regards non-material factors as a flimsy distraction we can afford to ignore; but they aren’t, and we can’t. The public needs to find a better way of expressing that; representatives of the system need to find a way of hearing it.

Some more articles on similar subjects that you might enjoy:

Good on the psychological consequences, but I think as a causal analysis (“focus on measurable vs unmeasurable blindness”) it doesn’t compute.

The actual migration Europe can attract, compared to other destinations, is of those who prefer higher welfare availability over lower taxes. Obviously this is biased towards those who expect to net receive!

Migration into Europe thus tends to depress per capita GDP; most extraeuropean immigration is received by countries having a hard time restricting the benefits package received by immigrants (duh):

Exactly the one that was not sustainable at the higher per capita net productivity of the autochthonous population, hence the GDP scramble.

Migration within Europe is more of a success story, but I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Now all of this would actually be easily measurable, but everyone except Denmark is studiously avoiding taking, let alone focussing, these obvious candidate KPIs, and France is even actively prosecuting those who try to measure them on their own. The problem here is clearly not what is measurable vs. what isn’t – because what’s measurable would point in the same direction, if only measuring it in a way that would allow gaining a holistic picture were not studiously avoided. It’s the literal joke of “we lose on every item, but we make it up in volume”, and it’s hard to take this refusal to look as an oversight.

Denmark looked at the actual overall picture, took action, and is now the ~only* West European country with a political system that is not permanently locked up in some version of cordon sanitaire and/or mutual radicalisation spirals on both sides. And yet nobody else seems to be imitating them. This is also hard to accept as an oversight.

* Except maybe here in Ireland – which has high discontent on this topic, as you have often noted, to no relevant electoral effect whatsoever, as you have often noted. We’re in a curious place.

Good article and comments. I think Chesterton is very relevant here too though, when it comes to explaining the actions of European and Irish: “When a religious scheme is shattered (…), it is not merely the vices that are let loose. The vices are, indeed, let loose, and they wander and do damage. But the virtues are let loose also; and the virtues wander more wildly, and the virtues do more terrible damage. The modern world is full of the old Christian virtues gone mad. The virtues have gone mad because they have been isolated from each other and are wandering alone. Thus some scientists care for truth; and their truth is pitiless. Thus some humanitarians only care for pity; and their pity (I am sorry to say) is often untruthful.”

Hope the relevance is clear. It’s a theological question in the end. (It often is.)

Also, I’m not completely convinced that there is a measurement deficit. Feelings among the population can be tracked (and put onto charts) through good polling data and voting patterns. I think the Chesterton quote may explain why these metrics are being ignored.