The Lifecycle of an Ally

The Gender Recognition Act 2015 is under attack, and the mainstream politicians who voted for it are running for cover. What happened?

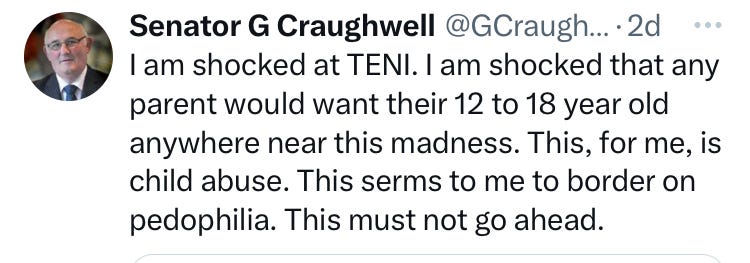

Independent Senator Gerard Craughwell has been on a tear for the last week. Craughwell is one of several Irish politicians who voted to introduce the Gender Recognition Act in 2015 who seem to be having doubts about it. The Act was one of the first in the world to introduce Gender Self-ID, allowing people to have their chosen identity legally recognised on the basis of declaration, and without medical evaluation. Craughwell’s turnabout has been more extreme than most:

On social media, he went from supporting the Act to fretting about it, to decrying it, to calling for its repeal in the space of a few days. The “TENI” he refers to above are a ubiquitous NGO who in the past have received a substantial amount of money from the government and were involved in the design of the legislation.

As a principle, it’s good for politicians to publicly admit they’ve changed their mind on an important subject, and we shouldn’t monster him for doing that. But since he’s not the only one who’s done so (more on that below), I think it is worth asking what happened between 2015 and today that caused the change. What was discussed in the Oireachtas during the extensive debates on the Act? Were any of the controversial topics touched on, and what was the result? My interest here is not the content of the law itself but the process that created it, and what that tells us about how laws like this are formed in Ireland and elsewhere.

I’ve posted some extracts from the final debates on the law below. The tldr here is that the Dáil and Seanad records show that many of the points politicians are now recoiling from were discussed in detail, though mostly not critically. Some concerns were not explicitly considered or refuted, but were touched on tangentially in a way that would have raised obvious questions for who gave any thought at all to the matter, which the legislators clearly did. As an explanation of how we got to this point, “we couldn’t possibly have known” isn’t really a sufficient explanation, and neither is “the facts changed so I changed my mind”.

The text of the final Seanad debate on the Act is here, and the final Dáil debate is here. The other debates are available, these two are the only ones I reviewed for this article.

To begin, one of the first people to speak in the final Seanad debate was Craughwell himself. He was (as he acknowledges) emotional about the passage of the bill, and regretted only that it had gone further. Emphasis in this and in all other passages is mine:

I feel extremely emotional as we draw this debate to a close. In a way we have had a great success today, but at the same time we have had a tremendous failure. I feel deeply sorry for the people in the Visitors Gallery tonight who had expected great things from us but who will walk away with heavy hearts. The Minister of State has done the best he can, for which I commend him. I am delighted that the Bill will pass. Alas and alack, like so many other things in this country, it will be revisited time and again. It will be tweaked, moved around and discussed, but people will shy away from it when it comes due for review. Not everybody is as brave and as strong as the Minister of State and the Tánaiste. Unfortunately, when the review time comes around I do not know whether either the Minister or I will be in this House, or any other House in this building. If the Minister of State is here, he will drive it as best he can and if I am here, I will also drive the review and try to bring the Bill closer to what our guests in the Visitors Gallery believe they sought.

I compliment all of my colleagues who spoke on the Bill. No one said anything against it. I compliment the Minister of State for bringing it to the House.

This point was echoed by Deputy Kevin Humphreys, the Minister of State who brought the Act before the Seanad. In doing so he explicitly highlighted that there were implications for the education system:

There is an element of education, of making people aware and of acknowledging that there are issues in the education system and society. It is important to recognise all citizens as equals. This work will be built on in the future; it is important and ground-breaking.

Again, the point here is not my own feelings about the law itself, or to dunk on someone changing their mind. But the above extract reflects an understanding found consistently throughout the debates - that the Act was a first step in a wider social change, not an end point; that any law passed should be expanded and liberalised in future, and that this expansion would be carried out through civic society groups and the state.

The mention of the education system makes it clear that the anticipated changes to the law were understood as having implications for children as well as adults. The rest of the debates reflect that: the final Seanad debate contains 29 references to “child”, and 62 to “children”. As an example of what was discussed, Senator Averil Power noted her dissatisfaction at the limited availability of Gender Recognition Certificates to children.

Power: I do not understand how the Minister of State could possibly think that it is not in the best interests of child if, to take the example of a 15 year old, he or she knows his or her true gender identity, his or her parents support him or her and want to have this recognised by the State and a judge could also be satisfied that this is in the young person's best interests.

A proposed amendment related to this aspect failed to pass, but the Minister of State sought to reassure Power and others by highlighting the extensive work being done in schools:

We are all concerned about the lived experience of transgender children in schools. I will confirm three relevant points on which we have worked over a period to improve the lived experience of transgender children in the school system… the Minister for Education and Skills, Deputy Jan O'Sullivan, recently met the parents of transgender children and has agreed to meet the Transgender Equality Network Ireland, TENI, over the next couple of weeks to discuss the lived experience of such children in schools and what policy options may be open. Third, following on from the meeting with TENI, the Minister is happy to convene a round-table discussion with all the educational partners on this topic. That will allow for the issues faced by transgender children and young people to be discussed in detail with the management bodies, with trade union representatives, students and parents. I trust this information is helpful.

What we all want to achieve is that the lived experience of children at school, complex as it is because of the school system we inherited over decades, is as positive as possible.

There is certainly no sense anywhere in the debates that a reasonable member of the public could have any level of concern with any of this stuff; or that if they did that their concerns were of any interest to the legislators.

That’s the Seanad; the Dáil for their part were no more inquisitive. And the turnaround from Senator Craughwell is nothing in comparison to that of Willie O’Dea.

O’Dea is a Fianna Fail TD for Limerick City, and it is within his constituency that Limerick Prison falls. This prison has been in the headlines lately because of the Barbie Kardashian case. When a group of women protested outside the Dáil carrying signs saying “No Males in Women’s Jails” O’Dea stopped by to show his support. How did O’Dea understand the legislation was making its way through the Oireachtas?

The record is particularly relevant because O’Dea was the first member of government to speak upon the introduction of the bill for its final reading in the Dáil. As such he was required not merely to assent to its passing but advocate for it; and that’s what he did, forcefully.

O’Dea was bullish on what he saw as the risk-free introduction of self-ID without any medical confirmation; and was very dismissive of any worries about the impact of this change:

Countries like Argentina and Denmark have allowed for self-determination. Malta, which is hardly an outstanding example of a democratic liberal democracy, is also proceeding in that direction. What has happened in those countries? Has the sky fallen in? Have their national debts doubled suddenly? Have they been reduced to a wasteland? No, what has happened is that vulnerable young people can now benefit from legislation which will in many cases alleviate their suffering during the period between when they realise they are living in the wrong gender and when they can get their gender officially recognised. Even that much maligned organisation, the HSE, which is hardly a bastion of liberalism, recognises that self-determination is the appropriate approach. I cannot for the life of me understand why the Government chose to ignore what other countries have done and what its own chief adviser in these matters, the HSE, recommends. The requirement for a professional medical examination seems to stigmatise people who are gender transitioning because it implies that such people need a third party to tell them who they are. Surely the individuals themselves are best placed to decide that.

Continuing this last point, he saved his deepest condemnation for those who believed medical professionals could play any role in gatekeeping how someone could legally identify, a belief he described as “paternalistic and condescending”:

Those under the age of 16 years are left in limbo. In many cases, people recognise the fact that they belong to a different gender at a very young age. In these cases, individual's experiences between the point where he or she realises he or she is the wrong gender and turning 16 years, or 18 years as will usually be the case, can be very difficult and potentially leave lasting scars. I will not refer to particular cases but the Minister of State, Deputy Kevin Humphreys, knows what I am speaking about. Why should somebody who has already transitioned have to wait until turning 16 years or, more likely, 18 years before the State recognises his or her true identity? It is paternalistic and condescending. It is not as if every six or seven year old in the country is going to rush to a registrar to get a gender transition certificate. Surely that is a matter their parents will take up, and it is certainly not something that would be done lightly. People will not take this step unless they genuinely feel they are in a different gender.

The one issue that isn’t raised anywhere that I can see is the impact of the Act on single-sex spaces. Neither biological sex gets mentioned much: in the Dáil record, the word “man” is used once, and the terms “men”, “woman” and “women” not at all. For the final Seanad debate, the term “women” was used once, but that’s it.

However the lack of focus on biological sex is not sufficient to explain why the issues weren’t discussed. All the concerns that arise in relation to single sex spaces are downstream from the Act's implicit adoption of “Gender Identity” as the correct way of looking at issues relating to sex. This in turn is what facilitates the Act’s version of self-ID. All of that *was* discussed.

Once you accept the philosophical proposition of Gender Identity and allow for Self-ID, it obviously creates tensions in existing arrangements in how the sexes interact. It may be that one feels such tensions represent a tiny number of edge cases that shouldn’t be given priority over the expansion of civil rights embodied by the Act. I understand that perspective. But the whole point of an extensive legislative process is to flush those kinds of dilemmas out and resolve them if possible.

Willie O’Dea isn’t the only politician whose stance on this issue has changed without admitting it. When Leo Varadkar was asked about the Kardashian case (by Gript: no mainstream outlet has the nerve), he first claimed ignorance, then indicated that the Act should be revised to ensure the matter could not reoccur.

Varadkar finishes his response to the question by saying “if the situation which arose in Scotland has now arisen in Ireland…” (He was referring here to the Isla Bryson case). It’s worth lingering over that sentence, because it reflects a really breathtaking level of disingenuousness on Varadkar’s part. He knows very well that treating someone in line with their legally declared identity - which is what happened in the Kardashian case - is not an unforeseeable side-effect of the Act: it’s a reflection that the Act is functioning exactly in line with its core purpose. His evasiveness is reflective of a wider evasiveness on the part of the legacy parties when it comes to owning the radical nature of the GRA and their support for that radicalism to date. Lots of activists were annoyed with him about that and they were right to be.

Compared to Varadkar and O’Dea, the least you can say about Craughwell is that he admits he’s changed his mind. The other two have switched from frothing Jacobins to timid counter-revolutionaries and have given no indication as to how they explain this change.

So, finishing up - what accounts for the change between 2015 and today? If legislators could reasonably have foreseen that the Act would get them into political trouble, how come that’s not reflected in the debates?

As I have noted above, the tone of the final debates is strikingly emotional with lots of references to families the legislators spoke to, people who have shared their experiences and activist groups who humanised the issues at hand. I believe this is sincere. But my sense is that while debating and discussing the Act, legislators relied heavily on representative groups who created a kind of emotional pressure cooker in which it was tricky to raise reservations without being seen as hard-hearted, bigoted or losing status amongst your colleagues and the media. I think lots of the legislators knew about issues like single-sex spaces but didn’t have the courage to press them.

I’ve probably over-emphasised the importance of activists in the Irish political system in the past. But I think it’s definitely true that on matters of social liberalisation, the “interested parties” who feed into a piece of legislation tend almost exclusively to be committed activists on the left side of the spectrum. Technical experts (the debates are suffused with references to them) are essential, but as humans they are drawn from the same social class and milieu as the activists. They often view their expertise first through the prism of that value system, which can make the expert view and the activist one more or less interchangeable.

Stepping back, it’s important to remember the social context of 2015 when the debates took place. The death of Savita Halappanavar was still fresh in politicians minds, as was the campaign for the legalisation of Gay Marriage. I would guess they reflected on these events, and speculated that facilitating the passage of self-ID was a quick way of getting your face in the frame of a historic photo. In 50 years (they thought) people will think of this as the great civil rights victory of our time. Better to err on the side of doing too much than too little.

Again, this view was probably encouraged by the ocean of activist subject matter experts surrounding them, darkly warning of the social consequences of aligning themselves with “rights-hoarding dinosaurs” on the wrong side of history. I’m sure politicians were also encouraged to believe that passing an expansive version of the law was both risk-free and noble.

The thing is, it *is* kind of noble to fight a sincerely held moral position in the teeth of public opinion. If the strident Willie O’Dea of 2015 had held his ground, I could live with that. Public support for the GRA was and is uncertain - but that makes it doubly impressive that any legislator might have heard the evidence, weighed the decision and decided to (in his mind) draw a line in the sand in defence of a vulnerable group. Some things are more important than going up in the opinion polls. But that’s not what happened.

To summarise: it’s ok, good even, to change your mind. I think we can acknowledge that, while agreeing that this is not an optimal way of passing laws; that it would be better if people understood the nuances of legislation before voting for it. Or, to put that more accurately, that people felt they had the psychological breathing room, critical advice and/or personal courage to do that.

Every aspect of the GRA that is causing discomfort or confusion either could have been anticipated and worked through; or actually was anticipated, and was dismissed without critical assessment. This includes the adoption of the philosophy of Gender Identity as the way our state understands men and women and how they relate to each other, the desire to educate the public on this changed understanding and the law generally, the relevance of the law (or not) for children, the impact on single-sex spaces for women, and the intention to use the law as a base from which to press for further change.

None of this is to argue against the law itself or any individual change in it, only against the process in which it was decided, a process that failed all parties in some way. It’s not good that people who had concerns about the profound and radical cultural shift contained in the GRA weren’t given a full hearing; but it’s also not good that extravagant promises were made to others about the future of the GRA as it became law, only for those promises silently recanted once the heat was on.

I don’t think it’s fair to blame partisan activists for that failure. It’s not their job to ensure their ideological opponents get airtime, and it’s not their problem that we’ve created a system in which that doesn’t happen with certain topics. That’s a problem for the wider public, and in political terms, for Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael as the closest thing we have to non-activist parties. On cultural issues, who knows what FF and FG’s values are, who they advocate for, what they actually want? A quiet life, the esteem of the right sort of person, and the chance to move up in the world, I suspect. If that was ever enough, it’s not anymore, so they may want to figure out a more robust, defensible way of deliberating on these kinds of decisions before events overtake them.

Same in Canada. Politicians got unprecedented numbers of submissions begging them not to pass gender bills. Well reasoned, well informed. I wrote some of them myself. They basically all voted yes, including the Conservatives now critiquing the outcomes we told them were the things that would be squished by the Squishing Things Act on which they voted yes.

A friend recently called her MP’s office and the person who answered assured her the MP in question does not and has never supported the policies for which the record shows yeah, he did vote for.

🙄

Minor point on the below but O’Dea was not a government TD in 2015

“The record is particularly relevant because O’Dea was the first member of government to speak upon the introduction of the bill for its final reading in the Dáil.“