The Problem With Videodrome Is That It Was Too Optimistic

What the prophetic 1983 movie got wrong about the future of media is more revealing and frightening than what it got right

I’ve been thinking about David Cronenberg’s 1983 movie Videodrome a lot recently; from what I see on my timeline loads of others have too, so I decided to revisit it and see how it stood up.

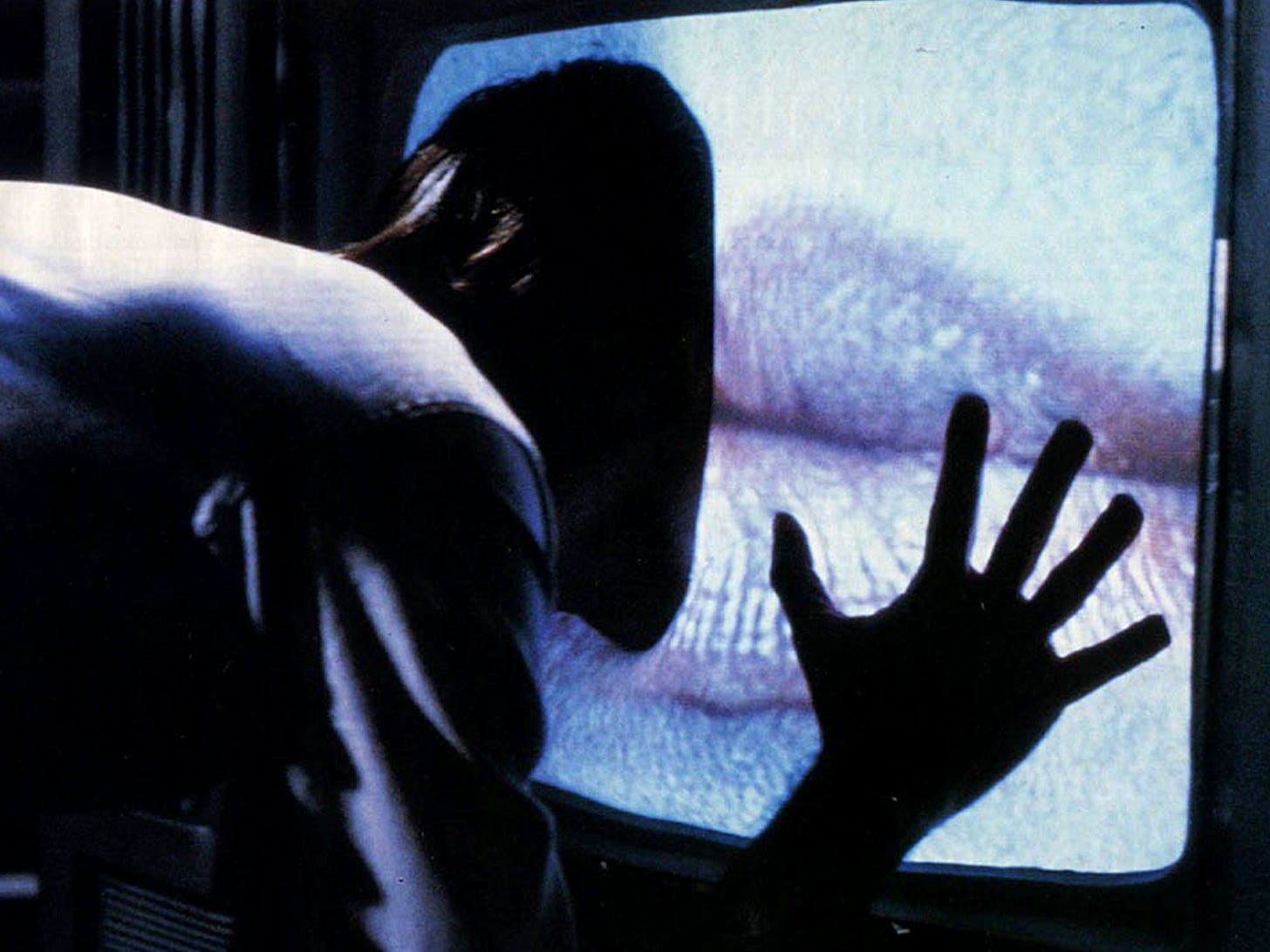

It’s not hard to see why it would hit a nerve with people online. The subject of the movie is people consuming media that makes them sick and crazy; people living in a depraved and hallucinatory digital dream-world; and how all of this distorts and dissociates us from normality as we begin to see our bodies and minds as media products, no different than what we consume.

Plot summary from Wikipedia for anyone who hasn’t seen it:

Set in Toronto during the early 1980s, it follows the CEO of a small UHF television station who stumbles upon a broadcast signal featuring violence and torture. The layers of deception and mind-control conspiracy unfold as he uncovers the signal's source, and loses touch with reality in a series of increasingly bizarre hallucinations… The film received praise for the special makeup effects, Cronenberg's direction, James Woods and Deborah Harry's performances, its "techno-surrealist" aesthetic, and its cryptic, psychosexual themes… Now considered a cult classic, the film has been cited as one of Cronenberg's best, and a key example of the body horror and science fiction horror genres.

What specific parts of the movie feel resonant today?

At the start of the film James Woods is leading a fetid and nocturnal lifestyle, horribly familiar from Covid times. He lives in an apartment with all the curtains drawn, falls asleep on his couch amidst a heap of junk food wrappers and pornographic photos, only waking up in the late evening to go out and get more ammo for this dream world.

A TV show host describes Woods as contributing to an atmosphere of “sexual malaise” which is a bracingly great description of the OnlyFans and TikTok era.

Brian O’Blivion, the elusive “media prophet” Woods seeks out during the movie, predicts the rise of online personas when he says that “O’Blivion is not the name I was born with… it’s a special name… soon all of us will have special names, designed to cause the cathode tube to resonate…”

O’Blivion’s daughter describes the performative media lifestyle of the Too Online when she says of her father that “(he ultimatley) believed that public life on TV was more real that private life in the flesh.”

Most memorably, Woods consumption of the Videodrome broadcast causes him to grow what can only be described as a vagina-like contusion in his stomach, through which he feeds videotapes (and a gun). I’m not going to draw any conclusions as to the implications of that image. I’ll leave that Abigail Shirer or Mary Harrington.

I don’t want to say “what it got wrong” because it was a movie, not a think-tank forecast; but for all it’s prophetic qualities, it’s what it didn’t foresee about the future that really struck me.

One of the things that’s almost charming and old-fashioned is that Woods really has work at his depravity. He has to go looking for gross evil stuff, for porn, gore and body-horror. He and the viewer experience an illicit thrill as he fulfils this quest.

Switching to the reality of online life today, the real quest is to avoid that stuff because you swim in it constantly. There’s no thrill in finding something that represents the most extreme behaviour or that prompts us revel in it because social media often feels like it consists of little else. (other than cute pictures of animals).

James Woods’ character, transported to our world, would be able to satiate his desire for the violent, the coarse and the insane in 15 minutes with access to a smartphone bought on the high street, a globally popular app and maybe a credit card; no journey to the underworld is necessary.

In Videodrome (the movie) there is an illicit thrill on the production side as well as the consumption side. Sinister forces are creating content they know is bad, and deforming, and they are secretive about it.

Switching to our world the difference is not merely that we are immersed in Videodrome style dissociative body-horror but that no one is embarrassed about it. Quite the opposite! The media sources most associated with upward mobility and respectable social status are the ones most likely to tell you (for example) that human biology is oppressive, arbitrary nonsense that can be discarded to embrace a New Flesh.

The vectors of the shittiest and most deforming aspects of popular culture aren’t sleazebags like James Woods but the aspirant classes, the people who wish to join them or provide services to them, and the companies they work for.

That in turn means that the frisson is gone for both producer and consumer because everything is bent to the style of the careerist and the social climber. Ours is the age of the clutched pearls and the sour look of disapproval, rather than the leer and the dirty raincoat - but we’re no more perverted for all that.

Videodrome correctly predicted how depraved and crazy our future would be; that technology would lock us in a self-disguising prison from which there is no escape, which changes our minds an bodies as we live in it. What it didn’t predict is how corporate this future would be, how banal and how insufferably pompous.

We have discovered what the makers of Videodrome wouldn’t have guessed - that human beings have unlimited tolerance for being commodified in body and spirit as long as it’s easy; and as long as the commodification is sold to them as a luxury good, and a marker of upward social mobility. And unfortunately for us, this is no hallucination.

You nailed this one. Woods as Max Renn has to descend into the criminal underground a la Orpheus -- and the character is fascinatingly ambivalent; is he really just trying to satisfy his own perverse desires or is he trying to be an investigative reporter/detective and solve a horrible crime?

"The signal's coming from somewhere around Pittsburgh." I think one of the piquant things about the movie is that the USA's general depravity is infecting Canada by osmosis, although Cronenberg himself might disabuse the notion; "I don't have a moral plan. I'm Canadian."

Now the criminal underground is delivered to us, virtually. Crime used to be hard work! I have respect for old-school criminals. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You_Can%27t_Win_(book)

If you haven't seen them yet, I recommend Cronenberg's FAST COMPANY and THE ITALIAN MACHINE. The man unironically loves fast cars and motorcycles.

Just gonna drop this here without comment: https://realitystudio.org/interviews/1992-burroughs-cronenberg/